Opioid Dose Risk Calculator

This tool calculates your morphine milligram equivalent (MME) dose to understand your overdose risk based on CDC guidelines. The article explains that doses above 50 MME/day show diminishing returns for pain relief but increase overdose risk significantly.

Have you or someone you know been on opioids for pain and noticed that the same dose doesn’t work like it used to? You’re not imagining it. This isn’t a sign the medication is failing-it’s opioid tolerance, a normal, predictable change in your body’s response to the drug. Over time, your brain and nervous system adapt. What once eased your pain now feels weaker. So, your doctor increases the dose. And then again. And again. This cycle isn’t rare. In fact, about 30% of people on long-term opioid therapy need higher doses within the first year. But here’s the part no one talks about: increasing the dose doesn’t always mean better pain control. It often just means more risk.

What Actually Happens Inside Your Body?

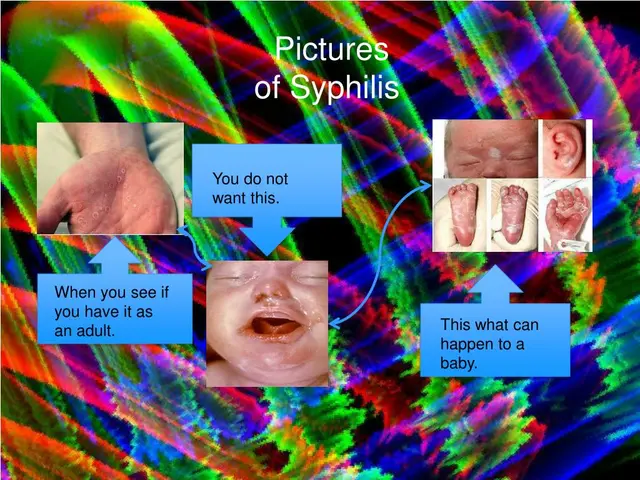

Opioids work by binding to special receptors in your brain, spinal cord, and nerves-mostly the mu-opioid receptor, coded by the OPRM1 gene. When they attach, they trigger a flood of dopamine. That’s what gives you pain relief, and sometimes, a sense of calm or even euphoria. But your body doesn’t like being constantly flooded. So it starts adjusting. First, the receptors get less responsive. They don’t send the same signal even when the drug is there. Then, some receptors pull back inside the cell, hiding from the drug. Over weeks or months, your body even starts making fewer receptors overall. This is called downregulation. It’s like turning down the volume on a speaker that’s always blasting. The sound is still there, but you need to crank it louder to hear it the same way. This isn’t just in your head-it’s physical. Studies show inflammatory pathways like TLR4 and NLRP3 inflammasomes get activated by long-term opioid use, making the nervous system more sensitive to pain and less responsive to the drug. That’s why some people feel more pain even as they take more pills. The system is stuck in overdrive trying to compensate.Tolerance Isn’t the Same as Dependence or Addiction

People often mix up tolerance, dependence, and opioid use disorder (OUD). They’re related, but they’re not the same thing. Tolerance means you need more of the drug to get the same effect. Dependence means your body has adapted to having the drug around. If you stop suddenly, you get withdrawal-sweating, shaking, nausea, anxiety. That’s your body screaming because it’s no longer used to functioning without it. Opioid use disorder is when the drug starts controlling your life. You keep using even when it hurts your health, relationships, or job. You might lie, hide pills, or risk legal trouble to get more. Tolerance can lead to dependence, and dependence can feed OUD-but not everyone with tolerance develops addiction. Many people take opioids for chronic pain and never lose control. But tolerance still puts them at risk.Why Dose Increases Are Dangerous

Raising the dose doesn’t fix the problem-it just pushes you deeper into danger. Higher doses mean higher risk of breathing problems, especially when mixed with alcohol, benzodiazepines, or sleep aids. The CDC warns that doses above 50 morphine milligram equivalents (MME) per day show diminishing returns for pain relief, but the risk of overdose jumps sharply. And here’s the hidden trap: tolerance can disappear. If you stop taking opioids-even for a few days during hospitalization, rehab, or incarceration-your body resets. Your receptors come back. Your sensitivity returns. That means if you go back to your old dose, you could overdose. That’s why 74% of fatal overdoses among people released from prison happen in the first few weeks. Their tolerance is gone. Their judgment isn’t. A 2020 study found that 65% of overdose deaths in recovery happened because people took the same dose they used before quitting. They didn’t realize their body had changed.

What Doctors Should Do-And What They Often Don’t

Good doctors know this. They don’t just keep increasing doses. They ask: Is this still helping? Are there other options? Could we try something non-opioid? Physical therapy? Nerve blocks? Antidepressants? Cannabinoids? Some of these work better for long-term pain than opioids ever did. The CDC recommends reevaluating treatment goals before crossing 50 MME per day. At 90 MME, the risk of overdose is more than double that of someone on 20 MME. Yet, many patients are still pushed toward higher doses because there’s no clear alternative in the system. Some clinics now use blood tests to check opioid levels, but that’s not enough. The real test is asking: Are you sleeping better? Moving more? Functioning at work? Or are you just numb?New Science: Can We Stop Tolerance Before It Starts?

Researchers are working on ways to block tolerance before it takes hold. One promising approach combines low-dose naltrexone with opioids. Naltrexone normally blocks opioids entirely-but at tiny doses, it seems to calm the inflammatory pathways that cause tolerance. Early trials show patients need 40-60% less dose escalation over time. The FDA is now encouraging drug makers to design new painkillers that don’t trigger tolerance as quickly. The goal isn’t to make stronger opioids-it’s to make smarter ones. Some experimental drugs are targeting specific receptor shapes or avoiding inflammatory triggers altogether. Another idea? Rotating opioids. If morphine stops working, switching to oxycodone or hydromorphone can sometimes reset the system. It’s not a cure, but it can buy time.

What You Can Do

If you’re on opioids:- Don’t assume a higher dose = better pain. Talk to your doctor about non-drug options.

- Keep a pain diary. Note what helps, what doesn’t, and how your mood and function change.

- If you’ve stopped opioids-even briefly-never go back to your old dose. Start with 25-50% of what you used to take.

- Ask about naloxone. It’s a life-saving overdose reversal drug. Keep it in your home, your car, your bag.

- Know your dose in MME. Ask your pharmacist to convert your pills to morphine milligram equivalents. That number tells you your risk level.

The Bigger Picture

In 2022, over 81,000 Americans died from synthetic opioids like fentanyl. Many of those deaths were tied to tolerance miscalculations. Someone on prescription oxycodone might think they’re used to strong drugs. Then they buy street pills that look identical-but contain 50 times more fentanyl. One pill. One mistake. One death. This isn’t about willpower. It’s about biology. Our bodies adapt. And when they do, the system often pushes us to do the one thing that makes things worse: take more. The real solution isn’t just better drugs. It’s better conversations. Better education. Better support for people who need pain relief without risking their lives. If you’re on opioids, you’re not alone. But you need to be informed. Because the dose you’re on today might not be safe tomorrow.Is opioid tolerance the same as addiction?

No. Tolerance means you need a higher dose to get the same effect. Addiction, or opioid use disorder, means you keep using the drug even when it harms your life-your health, relationships, or job. You can have tolerance without addiction, but tolerance can make addiction more likely.

Can opioid tolerance be reversed?

Yes, but only after stopping the drug. Your body naturally resets its opioid receptors over time-usually within days to weeks. But this is dangerous if you return to your old dose. That’s why people in recovery are at high risk of overdose. Their tolerance is gone, but their urge to use might not be.

Why do doctors keep increasing opioid doses?

Sometimes because they don’t have better tools. Many doctors are trained to treat pain with medication, not alternatives. When pain doesn’t improve, increasing the dose feels like the only option-even though research shows it often doesn’t help after a certain point. The CDC recommends reevaluating treatment goals before crossing 50 morphine milligram equivalents per day.

What’s the safest way to reduce opioid use?

Work with your doctor on a slow, personalized taper. Never stop suddenly. Combine tapering with non-opioid pain management-physical therapy, cognitive behavioral therapy, or medications like gabapentin or duloxetine. If you’re struggling, medications like buprenorphine or methadone can help reduce cravings and withdrawal.

If I’ve been off opioids for a while, how do I know if I’m at risk for overdose?

You’re at high risk if you return to your old dose-even if you feel fine. Your tolerance has dropped. Start at 25-50% of your previous amount. Use naloxone if you’re using alone. Never use alone. And if you’re using street drugs, assume every pill or powder could be laced with fentanyl. Your body doesn’t know the difference.

joe balak

November 3, 2025 AT 00:07Same dose stops working? Yeah that's just biology. Your body's not broken, it's adapting. Stop pretending higher doses mean better pain. They just mean higher risk.

Amina Kmiha

November 3, 2025 AT 19:20Of course they keep increasing doses 💀 The pharmaceutical industry doesn't want you to know that tolerance resets. They make billions off your desperation. You think this is science? It's profit. And now you're addicted to a system that profits from your pain. 🚨

Ryan Tanner

November 4, 2025 AT 09:44Been there. Started at 30 MME, ended up at 120. Didn't feel better. Just felt numb. Started PT, got a TENS unit, and cut down slow. Best decision I ever made. You're not weak for needing help. You're smart for looking for better options. 🙌

Sara Allen

November 5, 2025 AT 04:15so like... if you stop taking the pills your body just forgets how to handle pain? like its a reset button? but then you go back and boom overdose? that sounds like a trap set by the doctors and the pharma companies. i dont trust any of them. they just want to keep you hooked. and now theyre saying its your fault? no way. its their fault. they gave it to you and then acted surprised when you got addicted. 🤡

Cornelle Camberos

November 5, 2025 AT 07:24One must acknowledge the systemic erosion of medical ethics in the contemporary American healthcare apparatus. The normalization of opioid escalation constitutes a profound failure of clinical stewardship, wherein pharmacological intervention is prioritized over holistic, neurophysiologically-informed therapeutic paradigms. The data are unequivocal: dose escalation is not therapeutic-it is transactional. The patient becomes a revenue stream, not a human being. The FDA, CDC, and AMA have all tacitly endorsed this paradigm through inaction. One must ask: Who benefits? And why are we complicit?

Jessica Adelle

November 6, 2025 AT 20:12It is deeply troubling that the American public has been conditioned to view pharmaceutical dependency as an acceptable solution to chronic pain. This is not medicine. It is moral decay masquerading as care. The Founding Fathers did not envision a nation where citizens are chemically sedated to endure suffering rather than empowered to overcome it. We have abandoned resilience in favor of convenience-and now we pay with our lives. Shame on the institutions that allowed this to happen.

Emily Barfield

November 7, 2025 AT 14:33What is pain, really? Is it merely a biological signal-or is it a metaphysical echo of a broken system? We treat the symptom, not the soul. We flood the receptors, but ignore the loneliness, the trauma, the quiet despair that makes the body scream for relief. The opioid crisis isn’t about chemistry-it’s about abandonment. We’ve outsourced healing to pills because we’ve forgotten how to hold each other. And now, when the pills stop working, we don’t know how to sit with the silence anymore.

Iván Maceda

November 8, 2025 AT 15:03So the government lets Big Pharma push opioids, then when people get addicted, they blame the addicts? 🤦♂️ And now they want us to believe this is 'science'? Nah. This is a war on the poor. They give you the drug, then take away your benefits when you can't work. Then they lock you up for trying to get more. This isn't medicine. It's control. 🇺🇸

Rebecca Parkos

November 8, 2025 AT 22:23I lost my brother to this. He was on 60 MME for a back injury. Got laid off. Stopped for a month. Came back to his old dose. Didn’t make it. I don’t care what the studies say. I care that he’s gone. And no one warned him. No one told him his body would forget. Don’t let this happen to someone else. Ask for naloxone. Always. 🫂

John Rendek

November 10, 2025 AT 11:42Good post. Real talk. If you're on opioids, talk to your doctor about alternatives. Physical therapy, CBT, even acupuncture can help. Don't wait until it's too late. You're not alone in this. And you deserve better than a higher dose.

Ted Carr

November 11, 2025 AT 23:24Wow. A post that doesn’t end with ‘just say no.’ Who even are you? Some kind of medical wizard? 🤨 Next you’ll tell us water is wet and gravity isn’t a suggestion.

Sai Ahmed

November 12, 2025 AT 14:03They say tolerance resets. But what if they’re lying? What if the damage is permanent? What if your brain never recovers? Who’s to say the next dose won’t kill you? Who’s to say they didn’t engineer this? I’ve seen things. I know things.

Albert Schueller

November 12, 2025 AT 23:05Interesting that the article cites CDC guidelines, yet ignores the fact that many doctors are pressured by insurance companies to prescribe opioids rather than invest in physical therapy or mental health services. The system is rigged. The science is sound, but the implementation? Broken. And no one wants to fix it because it’s too expensive. Just another example of American healthcare prioritizing profit over people.

Vrinda Bali

November 13, 2025 AT 22:16It is not merely a biological phenomenon-it is an orchestrated deception. The opioid epidemic was not an accident. It was engineered by corporate interests, facilitated by regulatory capture, and normalized by cultural complacency. India, too, now faces the creeping shadow of this crisis. We must awaken. We must resist. We must demand accountability-not just from doctors, but from the silent architects of this tragedy.