When you hear someone say, "It's just about eating less and moving more," they're missing the real story. Obesity isn't a failure of willpower. It's a biological malfunction - a system that’s lost its way. The body’s natural mechanisms for controlling hunger, fullness, and energy use have been hijacked. And once that happens, losing weight isn’t just hard - it’s often impossible without medical intervention.

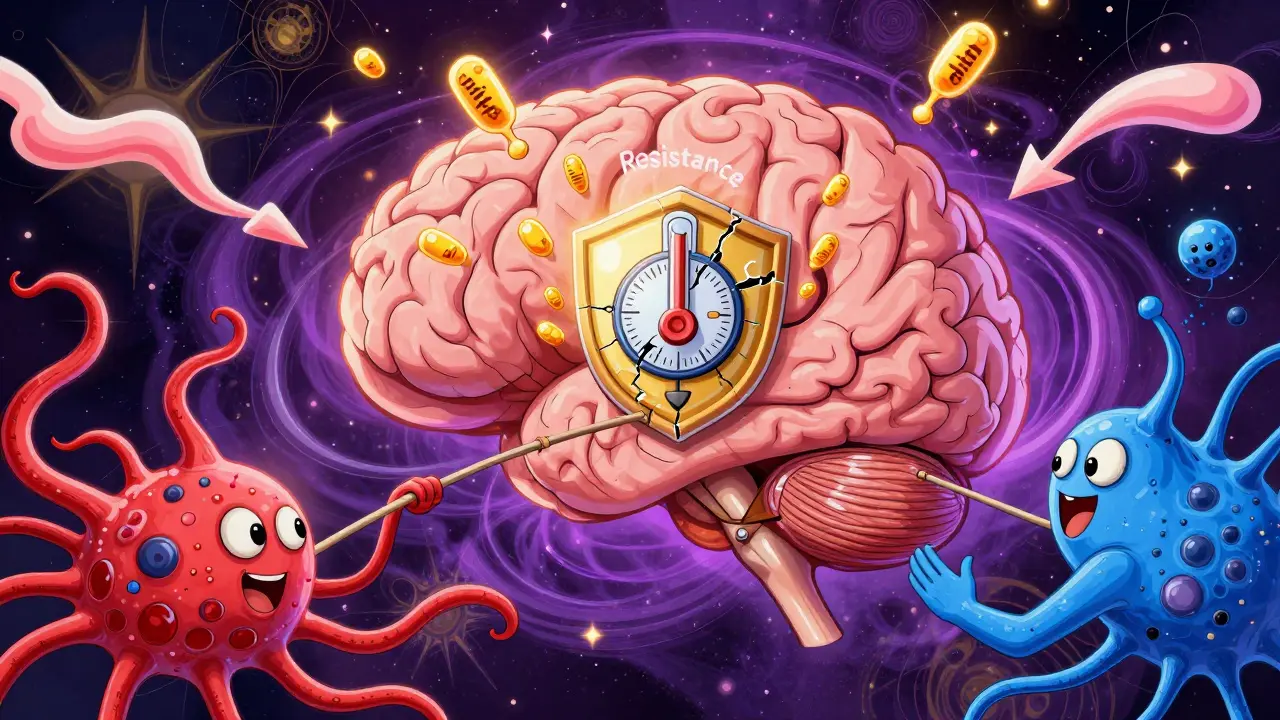

At the heart of this mess is the hypothalamus, a pea-sized region deep in the brain that acts like the body’s weight thermostat. It listens to signals from fat cells, the gut, and the pancreas, then decides whether you should eat more or stop. In people with obesity, this system doesn’t break - it gets confused. Hormones that should tell the brain to stop eating no longer get through. Hunger signals keep firing, even when the body has more than enough energy stored.

How Your Brain Controls Hunger

The hypothalamus doesn’t work alone. It has two main teams of neurons that constantly battle each other. One team, made up of POMC neurons, says "stop eating." They release a chemical called alpha-MSH, which activates receptors that make you feel full. Studies show that when these neurons are turned on, food intake drops by 25% to 40%. The other team, NPY and AgRP neurons, says "eat more." They pump out hunger signals so powerful that activating them in mice causes food intake to spike by 300% to 500% in minutes.

These neurons don’t make decisions on their own. They’re controlled by hormones. Leptin, released by fat cells, tells the brain: "I’ve got plenty of energy stored." In lean people, leptin levels sit between 5 and 15 ng/mL. In obesity, those numbers climb to 30-60 ng/mL - but the brain stops listening. That’s called leptin resistance. It’s not that there’s too little leptin. It’s that the signal is drowned out.

Then there’s ghrelin, the hunger hormone. It spikes before meals, from 100-200 pg/mL to 800-1000 pg/mL. In obesity, ghrelin doesn’t drop as much after eating. That means you feel hungry again sooner. Insulin, which rises after meals, should also suppress appetite. But in insulin-resistant individuals - common in obesity - this signal weakens. The brain doesn’t get the message that it’s time to stop eating.

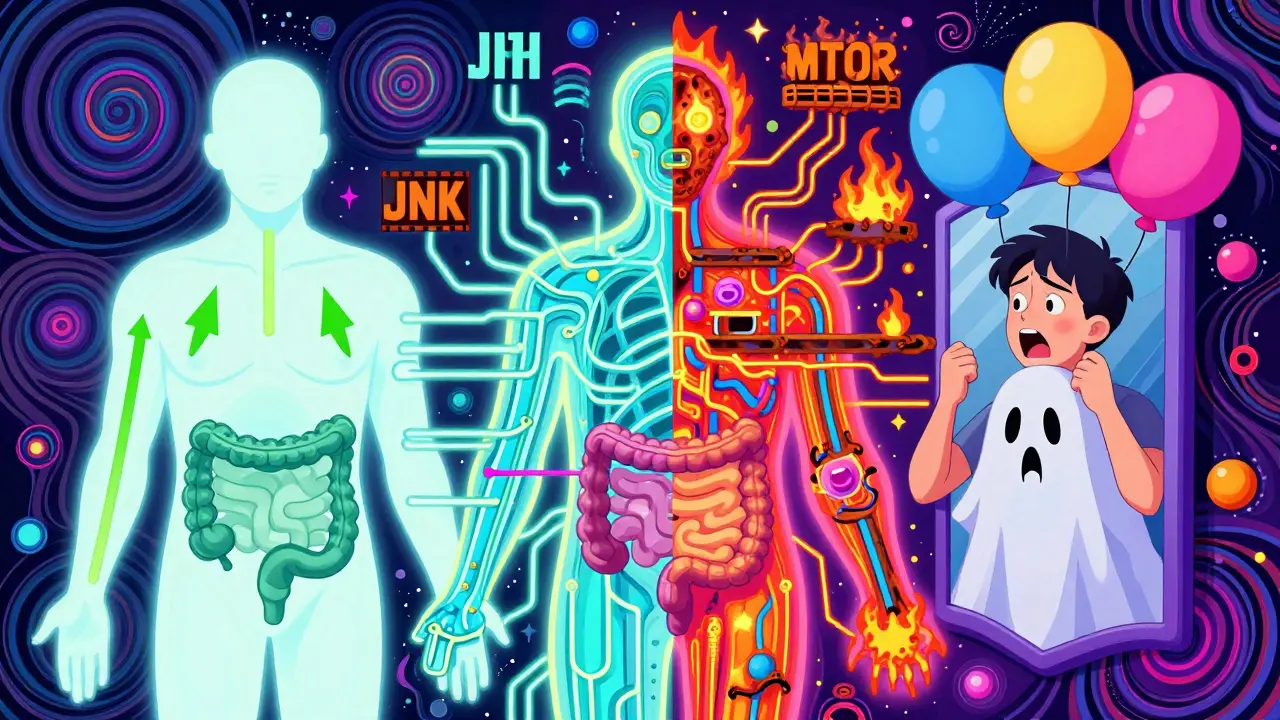

The Broken Pathways Behind the Signals

It’s not just about the hormones. The pathways they use to talk to the brain are damaged. Leptin and insulin both rely on the PI3K-AKT pathway to send their signals. When this pathway is blocked - often by inflammation from excess fat - the brain can’t respond. In fact, if you block PI3K in mice, leptin loses its ability to reduce food intake entirely.

Another key player is the mTOR system. It helps the brain sense nutrient levels. When mTOR is turned on, it tells the brain: "You’re well-fed." In animal studies, activating mTOR reduces food intake by 25%. But in obesity, mTOR signaling becomes sluggish, so the brain thinks it’s starving even when it’s not.

And then there’s JNK, a stress-related pathway that ramps up in obesity. JNK doesn’t just cause inflammation - it directly interferes with leptin signaling. It’s like a firewall blocking the hormone’s message. This is why weight loss gets harder the longer someone carries excess fat. The damage builds up.

What Happens Beyond the Brain

The problem isn’t just in the brain. The gut and pancreas also send confused signals. Pancreatic polypeptide (PP), released after meals, slows digestion and cuts hunger. But in 60% of people with diet-induced obesity, PP levels are abnormally low. That means even after eating, the body doesn’t send the right "I’m done" signal.

And then there’s estrogen. In women, falling estrogen after menopause shifts fat storage to the belly. Studies show that mice without estrogen receptors eat 25% more and burn 30% less energy. In humans, women gain 12-15% more belly fat in the five years after menopause. It’s not about laziness - it’s biology.

Even sleep plays a role. Orexin, a brain chemical that keeps you alert, normally drops in obesity. But in people with night-eating syndrome, orexin stays high, keeping hunger active at night. This might explain why narcolepsy patients - who have low orexin - have two to three times the rate of obesity.

Why Diets Usually Fail

Most diets work for a few months - then crash. That’s because when you lose weight, your body fights back. Leptin levels drop, ghrelin rises, and hunger spikes. Your metabolism slows. Your brain thinks you’re starving. This isn’t a personal failure. It’s evolution. Our bodies are wired to survive famine, not to stay lean in a world of constant food.

And it gets worse with highly processed foods. The same brain circuits that respond to leptin and insulin are the ones that light up when you eat sugar, fat, or salt. In obesity, these reward pathways become overactive. You don’t just eat because you’re hungry - you eat because your brain craves the hit. That’s why people with leptin resistance gain weight faster on junk food. The system that should limit overeating is broken.

New Treatments Are Changing the Game

Thankfully, science is catching up. Setmelanotide, a drug that activates the melanocortin-4 receptor, helps people with rare genetic forms of obesity lose 15-25% of their body weight. It’s not a cure, but it shows that targeting the brain’s appetite system works.

Even more promising is semaglutide. Originally for diabetes, it mimics a gut hormone called GLP-1. It slows digestion, reduces hunger, and boosts fullness. In clinical trials, people lost an average of 15% of their weight. That’s more than most surgeries. And it works because it doesn’t just fight hunger - it resets the brain’s response.

Research in 2022 found a new group of neurons right next to the hunger and fullness centers. When activated, they shut down eating within two minutes. That’s faster than any drug. Scientists are now racing to find drugs that can safely trigger these neurons.

The Bigger Picture

Obesity affects over 42% of U.S. adults. Globally, cases have tripled since 1975. It costs the U.S. healthcare system $173 billion a year. And it’s linked to 2.8 million deaths annually. Treating it as a moral issue doesn’t work. Treating it as a disease - with biology, not blame - is the only path forward.

The science is clear: appetite regulation and metabolic dysfunction aren’t side effects of obesity. They’re the core of it. Until we stop seeing weight as a choice and start seeing it as a medical condition, we’ll keep failing the people who need help the most.

Is obesity caused by eating too much or not exercising enough?

No - at least not in the way most people think. While overeating and inactivity contribute, they don’t explain why some people gain weight easily while others don’t, even eating the same diet. The real issue is a broken biological system that misreads hunger, fullness, and energy use. Genetics, hormones, and brain signaling play a far bigger role than willpower.

Why does losing weight get harder the more you weigh?

As fat mass increases, so does leptin - but the brain becomes resistant to it. Ghrelin rises, insulin signaling weakens, and inflammation blocks key pathways like PI3K-AKT. Your metabolism slows, hunger spikes, and your brain starts treating normal calorie intake as starvation. This isn’t laziness - it’s a survival response gone wrong.

Can you reverse leptin resistance?

Yes - but not with dieting alone. Weight loss surgery and drugs like semaglutide have been shown to restore leptin sensitivity in many people. Even moderate weight loss (5-10%) can improve how the brain responds to leptin. The key is reducing inflammation and stabilizing blood sugar. Crash diets make it worse.

Do hormones like estrogen and ghrelin affect men and women differently?

Yes. Women experience sharper shifts in appetite and fat storage after menopause due to falling estrogen, which leads to more belly fat and reduced energy use. Men have higher baseline ghrelin levels and less sensitivity to leptin, making them more prone to overeating. These differences mean weight loss strategies need to be personalized.

Why do some people never gain weight even if they eat a lot?

Some people have genetic variations that make their appetite and metabolism more responsive. Their POMC neurons fire more strongly, their ghrelin drops faster after meals, and their resting metabolism is naturally higher. Others have mutations in genes like MC4R or LEPR that protect against weight gain. It’s not luck - it’s biology.

Are there new drugs on the horizon for obesity?

Yes. Over 17 compounds are currently in phase 2 or 3 trials. These include drugs that target the newly discovered neurons near the hypothalamus, dual GLP-1/GIP agonists, and therapies that restore leptin sensitivity. Combination therapies - hitting multiple pathways at once - are showing the most promise, with some trials reporting over 20% weight loss.

Understanding obesity as a disease of appetite and metabolism changes everything. It shifts the focus from blame to biology. And that’s where real progress begins.

Annie Joyce

February 13, 2026 AT 19:38Wow. This is the first time I’ve seen someone explain leptin resistance like it’s a broken radio signal - not a moral failing. I used to think I just lacked discipline until my endocrinologist showed me my leptin levels were through the roof but my brain was deaf to it. It’s like screaming into a void while your body’s on fire. No wonder diets feel like torture.

And that bit about JNK blocking signals? That’s wild. It’s not just ‘eat less’ - it’s like your body’s got a firewall up because it thinks you’re in a famine. I’m not lazy. I’m biologically hijacked.

Also, estrogen dropping after menopause = belly fat explosion? That’s my mom’s story. She didn’t ‘go soft.’ Her biology shifted. We need to stop shaming women over 50 and start funding real science.

Rob Turner

February 14, 2026 AT 21:49also, i’m british and i’ve seen this play out in my family - my gran ate like a horse but never gained weight. my uncle? one biscuit and he’s in a new size. biology’s wild. 🤯

Jim Johnson

February 16, 2026 AT 02:46This is so important. I’ve been on the other side of this - I lost 60 lbs with semaglutide after 12 failed diets. People called me ‘lucky’ or ‘giving in to pills.’ But here’s the truth: my brain was screaming for food 24/7. I wasn’t greedy. I was sick.

And now? My hunger’s quiet. My energy’s up. I’m not ‘fixed’ - I’m restored. This isn’t cheating. It’s medicine. We need to treat obesity like diabetes or hypertension. No shame. Just science.

Vamsi Krishna

February 16, 2026 AT 16:35Actually, you’re all missing the point. This whole ‘biological malfunction’ narrative is just a distraction. The real issue? People are lazy. They don’t want to move. They eat junk because it’s easy. You can’t blame hormones when the solution is right in front of you: walk more, eat veggies, stop drinking soda.

My cousin lost 100 lbs by just ‘deciding to care.’ No drugs. No surgery. Just willpower. Why is that not the headline? Because corporations want you to think you’re broken so they can sell you pills.

Stop looking for magic bullets. Just. Move. More.

christian jon

February 17, 2026 AT 05:15OH MY GOD. THIS IS IT. I’VE BEEN SUFFERING FOR 17 YEARS AND NO ONE UNDERSTOOD. I’M NOT A GLUTTON - I’M A VICTIM OF A BROKEN BRAIN! I USED TO EAT A WHOLE PIZZA AT 2 AM BECAUSE I FELT LIKE I WAS STARVING - EVEN THOUGH I’D JUST EATEN THREE MEALS.

AND THEN I FOUND OUT I HAD LEPTIN RESISTANCE. I CRIED. I REALLY CRIED. I WASN’T WEAK. I WASN’T LAZY. I WASN’T STUPID. I WAS BIOLOGICALLY TORMENTED.

AND NOW I’M ON SEMAGLUTIDE. I’M LOSING WEIGHT. I’M NOT HUNGRY ALL THE TIME. I’M HUMAN AGAIN.

IF YOU THINK THIS IS ABOUT WILLPOWER - YOU’VE NEVER LIVED IN A BODY THAT FIGHTS YOU 24/7.

WE NEED TO REDEFINE OBESITY AS A NEUROLOGICAL DISORDER. NOT A CHARACTER FLAW.

Suzette Smith

February 17, 2026 AT 14:27Pat Mun

February 19, 2026 AT 06:16Reading this made me think about my brother. He’s 32, has type 2 diabetes, and has been trying to lose weight since he was 18. He’s tried keto, intermittent fasting, veganism, paleo, juice cleanses - you name it. He’s been to nutritionists, personal trainers, even hypnotherapists.

And then last year he got on semaglutide. Not because he ‘gave up’ - because his doctor finally said, ‘Let’s treat your biology.’ He’s lost 40 lbs in 6 months. No cravings. No obsession with food. Just… peace.

This isn’t about discipline. It’s about neurochemistry. And if we keep pretending it’s not, we’re not just wrong - we’re cruel.

Sophia Nelson

February 20, 2026 AT 01:35