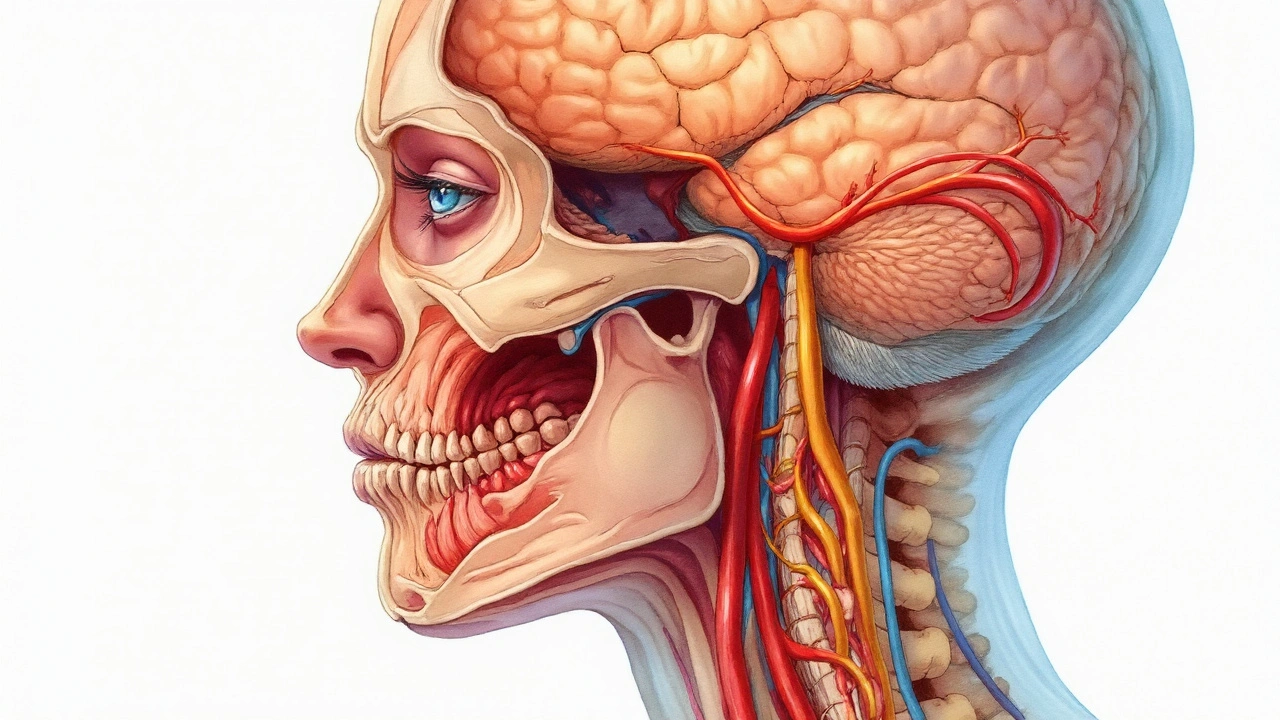

Idiopathic Orthostatic Hypotension is a persistent drop in blood pressure upon standing without an identifiable cause, characterized by a systolic decline of at least 20mmHg or a diastolic decline of 10mmHg within three minutes of upright posture. It belongs to the broader class of autonomic disorders and often co‑exists with other neuro‑vascular conditions. While standing, the body normally activates the Autonomic Nervous System, a network that modulates heart rate, vascular tone, and blood distribution. When this system falters, cerebral perfusion can dip, triggering headaches that share many features with Migraine, a recurrent neurovascular disorder marked by throbbing head pain, photophobia, and nausea.

Why Patients Notice a Link

Clinicians report that up to 30% of people with idiopathic orthostatic hypotension (IOH) also suffer from migraine‑type headaches. The overlap isn’t coincidence; both conditions involve the Trigeminovascular System, a pathway that releases vasoactive peptides (like CGRP) leading to vessel dilation and pain. When blood pressure falls, the brain’s Cerebral Blood Flow drops, prompting the trigeminovascular system to react, which can ignite a migraine attack.

Physiological Chain from Standing to Headache

- Orthostatic stress: Gravity pools blood in the lower limbs.

- Baroreceptor response: Sensors in the carotid sinus and aortic arch detect the pressure drop and signal the brainstem.

- Impaired reflex: In IOH, the sympathetic surge is blunted, so heart rate and vascular resistance don’t rise enough.

- Reduced cerebral perfusion: The Neurovascular Coupling mechanism fails to maintain adequate flow, especially in the posterior circulation.

- Trigeminovascular activation: Ischemia stimulates nociceptive fibers, releasing CGRP and substance P, which cause the classic migraine cascade.

This cascade explains why a simple act of standing can set off a pounding headache in susceptible individuals.

Diagnostic Tools That Connect the Dots

Two tests are especially useful when clinicians suspect a link between IOH and migraine:

| Test | Primary Target | Key Metric | Relevance to Both Conditions |

|---|---|---|---|

| Tilt Table Test | Blood pressure response to controlled tilt | Systolic/diastolic drop >20/10mmHg | Identifies orthostatic intolerance that can precipitate migraine attacks |

| Transcranial Doppler | Cerebral blood flow velocity | Mean flow velocity change >15% on tilt | Shows perfusion deficits that correlate with headache onset |

| CGI‑CGRP Blood Test | Calcitonin gene‑related peptide level | Elevated >50pg/mL during attacks | Links trigeminovascular activation to orthostatic drops |

When the tilt table test reveals a marked hypotensive response, and transcranial Doppler shows concurrent cerebral hypoperfusion, clinicians have objective evidence tying the two conditions together.

Treatment Strategies That Address Both Issues

Because the mechanisms intersect, therapies often hit two birds with one stone:

- Volume expansion: Fludrocortisone or high‑salt diet raises plasma volume, improving orthostatic BP stability and reducing headache frequency.

- Midodrine: An alpha‑agonist that contracts peripheral vessels, boosting standing BP and dampening the trigeminovascular trigger.

- Lifestyle adjustments: Gradual positional changes, compression stockings, and regular aerobic exercise improve autonomic tone and have been shown to cut migraine days by 20‑30% in IOH cohorts.

- Targeted migraine medication: CGRP antagonists (e.g., erenumab) not only abort migraines but may also modulate vascular tone, offering secondary benefit for orthostatic symptoms.

- Neuromodulation: Non‑invasive vagus nerve stimulation can enhance baroreceptor sensitivity, stabilizing BP and lowering migraine intensity.

Importantly, any pharmacologic plan should start low and go slow, monitoring BP trends with a home sphygmomanometer to avoid overshoot hypertension.

Potential Pitfalls and Red Flags

While most patients tolerate the combined approach, watch out for:

- Supine hypertension from excessive midodrine dosing.

- Electrolyte imbalance (hypokalemia) from fludrocortisone.

- Secondary causes masquerading as idiopathic - e.g., adrenal insufficiency, neuropathic autonomic failure, or medication‑induced hypotension.

If headaches persist despite optimal BP control, reassess for alternative migraine triggers such as hormonal shifts, sleep disorders, or dietary factors.

Related Topics Worth Exploring

Understanding the IOH‑migraine link opens doors to a broader set of conditions. Readers may also want to learn about:

- Vasovagal Syncope - another orthostatic‑related fainting event that shares autonomic pathways.

- Postural Tachycardia Syndrome (POTS) - a counterpart where heart rate spikes instead of BP dropping.

- Genetic Predisposition - emerging studies link specific SCN5A and MTHFR variants to both IOH and migraine susceptibility.

- Cerebrovascular Reactivity - how blood vessels respond to CO₂ changes, a useful research angle for clinicians.

Each of these topics nests within the larger umbrella of autonomic and neurovascular health, forming a natural next‑step reading path.

Frequently Asked Questions

Can standing up really trigger a migraine?

Yes. In people with idiopathic orthostatic hypotension, the sudden drop in blood pressure reduces cerebral perfusion, which can activate the trigeminovascular system and start a migraine attack. The effect is most noticeable within minutes of standing.

How is idiopathic orthostatic hypotension diagnosed?

The gold‑standard test is a tilt‑table study. Blood pressure is recorded supine, then after a 60‑ to 90‑degree tilt for up to 10minutes. A sustained fall of ≥20mmHg systolic or ≥10mmHg diastolic confirms the diagnosis when no secondary cause is found.

Do migraine medications help with low blood pressure?

Some newer CGRP‑targeting drugs have mild vasoconstrictive properties, which can modestly support blood pressure. However, they are not replacements for dedicated orthostatic treatments and should be used under a doctor’s supervision.

What lifestyle changes reduce both conditions?

Stay hydrated, increase salt intake (if no heart disease), rise slowly from sitting or lying, wear compression stockings, and incorporate regular low‑impact cardio such as walking or cycling. These steps improve autonomic tone and lower migraine frequency.

When should I see a specialist?

If you experience faintness, blurred vision, or a headache lasting more than 24hours after standing, or if home blood‑pressure logs show persistent drops, schedule an appointment with a neurologist or autonomic specialist for comprehensive evaluation.

Jessica Martins

September 25, 2025 AT 00:15Thank you for the thorough overview. The connection between orthostatic hypotension and migraine is indeed intriguing. I appreciate the clear explanation of the physiological cascade and the diagnostic tools presented.

Doug Farley

September 29, 2025 AT 19:44Great, another post telling us what the doctors already know. Because we all love reading about blood pressure drops while standing.

Jeremy Olson

October 4, 2025 AT 15:13The article provides an excellent synthesis of the current understanding of idiopathic orthostatic hypotension and its comorbidity with migraine. From a pathophysiological perspective, the shared involvement of the trigeminovascular system offers a plausible mechanistic bridge. Particularly noteworthy is the emphasis on cerebral perfusion deficits as a trigger for migraine attacks in susceptible individuals. Clinicians may find the inclusion of the tilt‑table test and transcranial Doppler especially valuable for objective assessment. In practice, I have observed that patients who demonstrate a clear drop in mean flow velocity during tilt often report a higher frequency of migraine days. The discussion of CGRP levels aligns with recent literature suggesting that autonomic dysregulation can potentiate neuropeptide release. Moreover, the therapeutic options outlined-volume expansion, midodrine, and CGRP antagonists-reflect a rational, multimodal approach. It is important to individualize the dosing of fludrocortisone, monitoring for electrolyte disturbances such as hypokalemia. Similarly, careful titration of midodrine can mitigate the risk of supine hypertension, a commonly reported adverse effect. The recommendation for compression stockings and gradual positional changes is a practical, low‑cost intervention that should be emphasized early in management. I would also suggest incorporating regular aerobic exercise, as it has been shown to improve autonomic tone and may reduce migraine burden. From a research standpoint, prospective studies evaluating the impact of vagus nerve stimulation on both blood pressure stability and migraine intensity would be highly informative. Future investigations might explore genetic markers, such as SCN5A variants, to identify patients at risk for combined IOH‑migraine phenotypes. Given the potential for overlapping pharmacotherapy, clinicians should be vigilant about drug interactions, particularly when prescribing beta‑blockers or other antihypertensives. Patient education regarding hydration, salt intake, and early symptom recognition remains a cornerstone of effective care. Overall, the article serves as a comprehensive reference that can guide both clinical assessment and therapeutic decision‑making.

Ada Lusardi

October 9, 2025 AT 10:41Sounds like a solid plan 😊

Pam Mickelson

October 14, 2025 AT 06:10Loved the clear breakdown-thanks for making a complex topic easy to digest!

Joe V

October 19, 2025 AT 01:39I suppose the author finally realized that low blood pressure isn’t just a boring number on a cuff. Still, the list of treatments reads like a pharmacy catalog. Perhaps a bit more focus on lifestyle would have been nice.

Scott Davis

October 23, 2025 AT 21:07Good summary, especially the part about compression stockings.

Calvin Smith

October 28, 2025 AT 15:36Wow, who knew standing could be a migraine‑triggering sport? Guess we’ll all be sitting like statues from now on.

Brenda Hampton

November 2, 2025 AT 11:05The link between CGRP and orthostatic drops is fascinating. Definitely worth sharing with my migraine support group.

Lara A.

November 7, 2025 AT 06:33They don’t want you to know that the big pharma drugs are just a way to keep us dependent!!!

Ashishkumar Jain

November 12, 2025 AT 02:02Bro, this is mind blowing, like a fresh perspective on why my head hurts after I stand up. Keep spreading such info, it helps many of us out there. Stay blessed!

Gayatri Potdar

November 16, 2025 AT 21:31Wake up! All these “clinical studies” are just smoke screens to push their hidden agendas.

Marcella Kennedy

November 21, 2025 AT 16:59I totally get how frustrating it can be to deal with both dizziness and pounding headaches; it feels like your body is playing a cruel joke. What really helps me is keeping a detailed log of my blood pressure trends alongside headache diaries, so I can spot patterns. Also, never underestimate the power of a good night’s sleep and gentle yoga-both seem to calm the nervous system. Remember, you’re not alone in this, and there’s a community ready to support you.

Jamie Hogan

November 26, 2025 AT 12:28One must appreciate the scholarly rigor of the explanation whilst noting the occasional lapse into layman phrasing. Still the overall synthesis remains commendable.

Ram Dwivedi

December 1, 2025 AT 07:57Great overview! 👍 The integration of pharmacologic and non‑pharmacologic strategies is spot on.

Mikayla May

December 6, 2025 AT 03:25Thanks for the concise recap of treatment options.

Jimmy the Exploder

December 10, 2025 AT 22:54Another generic write‑up that rehashes textbook content. Nothing new here

Robert Jackson

December 15, 2025 AT 18:23It is imperative to recognize that the interplay between autonomic dysregulation and neurovascular activation is underpinned by complex molecular pathways. Neglecting this nuance leads to suboptimal therapeutic regimens.

Robert Hunter

December 20, 2025 AT 13:51From a global health perspective, accessibility to tilt‑table testing remains a challenge in low‑resource settings. Advocacy for affordable diagnostic tools is essential.

Shruti Agrawal

December 25, 2025 AT 09:20Well structured article concise and clear. Appreciate the focus on practical management.